Consumers are going to be hit with hundreds of dollars of extra costs in the first year alone when Canada’s federally mandated carbon pricing schemes come into effect, says an economic think-tank.

“It will be about $250 in the first year,” said Alicia Macdonald, a principal economist with the Conference Board of Canada. “Those that are living paycheque to paycheque will feel the cost increase the most.”

In a report entitled The Cost of a Cleaner Future: Examining the Economic Impacts of Reducing GHG Emissions, the board’s economists break down the blow to consumers with the arrival of carbon tax in Canada’s bid to cut its greenhouse gas emissions.

The estimated final tally for each Canadian household is $2,500 annually in added costs to goods and services due to carbon pricing schemes by the year 2025.

Although the federal government is only requiring provinces to initially come up with schemes to add an extra $10 per tonne to the cost of carbon, Ottawa is also insisting that cost must go up to $50 per tonne by 2022. In their scenario, the board’s economists have projected it will rise to $80 per tonne by 2025 and drive up the costs of many things used by the average household.

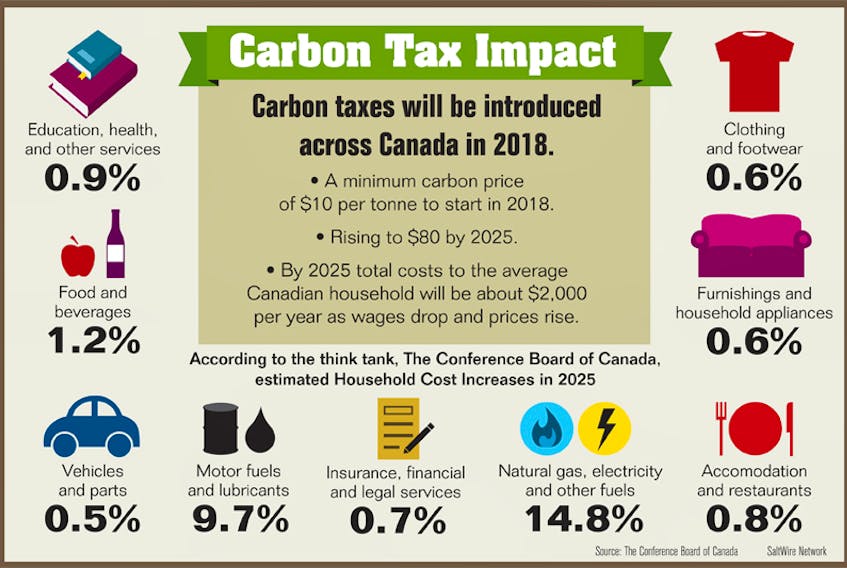

Natural gas, electricity and other fuels are expected to jump by 14.8 per cent due to carbon pricing schemes alone by 2025, according to the board. Motor fuels and lubricants – think a fill-up at the pump – are forecast to go up by 9.7 per cent for the same reason.

And that extra cost to move goods combined with the phasing out of coal-generated electrical production is expected to have a ripple effect through the economy.

Carbon pricing schemes are expected to up the cost of dining in restaurants and staying in hotels and motels by 0.8 per cent, increase the cost of furnishings, household appliances, and clothing and footwear by 0.6 per cent, say the economists.

“You can buy different things and prefer things that take less carbon … Demand for things changes when you make them more expensive.”

Buying insurance, getting financial services or using a lawyer is forecast to cost 0.7 per cent more by 2025 due to carbon pricing. Even government-provided services such as education and healthcare are expected to nudge up by 0.9 per cent.

The average Nova Scotian household’s grocery bill can expect to climb by 1.2 per cent – or about $97 – due to carbon pricing alone by 2025, according to the Conference Board’s forecast.

Not so, say others.

Dale Beugin, executive director at Canada’s Ecofiscal Commission, dismisses the Conference Board’s forecast on the impact of carbon pricing, saying it fails to account for the likely shift in consumer buying habits as a result of some things suddenly costing more and others relatively less.

“It’s a vast over-estimate of the cost to the economy and also to households,” said Beugin. “It doesn’t account for the carbon pricing plan to do what it is supposed to do.

“It’s assuming that people will just pay it and not change their behaviour,” he said. “You can buy different things and prefer things that take less carbon … Demand for things changes when you make them more expensive.”

Few details revealed on Atlantic Canada carbon plans

Provincial leaders are varying their approaches to dealing with meeting Ottawa’s carbon goals.

So far, British Columbia has led the way with the broad-based taxing of carbon, putting its own plan in place a decade ago. It started with a carbon tax of $10 per tonne and gradually raised it to $30 per tonne by 2012.

Quebec and Ontario have instead opted to go with cap-and-trade programs. These allow industry to buy and sell emissions allowances issued by those provinces and trade them on an open market that also includes the state of California. Those allowances are currently trading at about $18.50 per tonne.

In Alberta, the provincial government has chosen to implement a hybrid plan incorporating both a carbon tax and a cap-and-trade program.

But in Atlantic Canada, few of the details of each province’s carbon pricing schemes have been revealed.

“The goal is not to ask more from taxpayers; it is to ensure we are using taxation derived from fuel and industrial emissions to invest back into addressing climate change.”

New Brunswick's provincial government proposed in December to shift some of the amount it already collects as a gas tax at the pump over to a carbon tax and increase that portion gradually over the years to meet Ottawa’s demands. That money is to be put into a climate change fund to undertake measures to reduce emissions.

“The goal is not to ask more from taxpayers; it is to ensure we are using taxation derived from fuel and industrial emissions to invest back into addressing climate change,” said Environment and Local Government Minister Serge Rousselle in a statement. “This approach is about managing our existing revenue and investing in a more targeted way.”

Critics, though, have slammed the move, saying it fails to create new revenue to fight climate change. They also allege this scheme is unlikely to get the nod from Ottawa.

Maybe so – but that’s not keeping Newfoundland from considering a similar approach. A Newfoundland department of finance official has said the plan there is to phase in a carbon tax while phasing out the gas tax. That province is eager to reassure Newfoundlanders any carbon tax will be sensitive to any impact on vulnerable populations and consumers and be guided by the need to safeguard the competitiveness of onshore and offshore industry

Prince Edward Island officials are keeping mum on their carbon pricing plan, saying only that they are in negotiations with Ottawa.

Of the four Atlantic Provinces, Nova Scotia is the only one that has come out with a proposal in line with central Canada.

“In Nova Scotia, we’re developing a cap-and-trade program, largely modelled on Quebec and Ontario – but that is not to say we will be going with them right away,” said Jason Hollett, the province’s executive director of climate change. “The government has not committed to anything at this point. We’re still in policy development.”

Without the details of various carbon pricing programs in Atlantic Canada, the specific impact in any given province is still impossible to gauge with certainty.

Lower income households could see some payback from carbon tax

Low income households could see some of the carbon tax revenue back into their coffers.

According to Dale Beugin, executive director at Canada’s Ecofiscal Commission it’s very likely provincial governments will return at least some of the money collected through any carbon pricing scheme back to the lower-income groups.

That’s what British Columbia did, giving back carbon revenue to the poorest 40 per cent of households in that province. Alberta is giving back money to the bottom 60 per cent of households.

“Every province has the choice to use those resources as it wishes,” said Beugin.

Among economists, the consensus is the bulk of carbon tax revenues will be plowed back into personal and corporate tax cuts and new infrastructure spending to meet the Canada's emissions reduction targets.

“In our analysis, we assumed that 50 per cent of emissions revenues will be given back in the form of provincial personal and corporate income tax cuts, 40 per cent will go to additional public investment spending, and 10 per cent will go to lifting public sector spending to cover higher administration costs,” said Alicia Macdonald, a principal economist with the Conference Board of Canada.

With that boost to public spending to cut greenhouse gas emissions, Beugin is confident new technologies will be developed to meet Ottawa’s targets and this will create jobs and generate economic activity to offset any losses in the industries hurt by a price on carbon.

In Clearing the Air: How Carbon Pricing Helps Canada Fight Climate Change, Beugin wrote in early April this year that British Columbia’s experiment with a carbon tax has had little or no impact on the economy and helped cut greenhouse gases.

"Eroded purchasing power also results in households and businesses cutting their spending, and it is therefore no surprise that other commercial services .... (including) accommodation and food services, administrative support, and arts, entertainment, and recreation ... also fall significantly."

“Since 2008, British Columbia’s economy has outperformed the rest of Canada,” he wrote. “This difference doesn’t mean that the carbon tax is the reason for British Columbia’s higher growth … but it does reinforce that the tax likely wasn’t a significant barrier.”

The Conference Board's assessment isn't quite as rosy. Its economists are forecasting the residential construction, finance, insurance, and real estate sectors will be hit hard by a carbon tax.

"Eroded purchasing power also results in households and businesses cutting their spending, and it is therefore no surprise that other commercial services .... (including) accommodation and food services, administrative support, and arts, entertainment, and recreation ... also fall significantly," the board noted of its scenario with the lowest level of carbon pricing of the three described in The Cost of a Cleaner Future report.

The utilities and transportation sectors are also expected to see a downturn with carbon pricing and wholesale and retail trade is expected to soften, forecasts the board.

There will, however, also be winners under a carbon price regime. The board sees these as being the construction industry due to higher government spending, public administration, and the professional, scientific and technical services sectors.